Club History

Great Baltimore Fire

1904

It started on Sunday morning, February 7, 1904, supposedly when a lighted cigarette was dropped through a grating in front of the John E. Hurst Company’s warehouse. From the ashes of this disaster would spring the ESB.

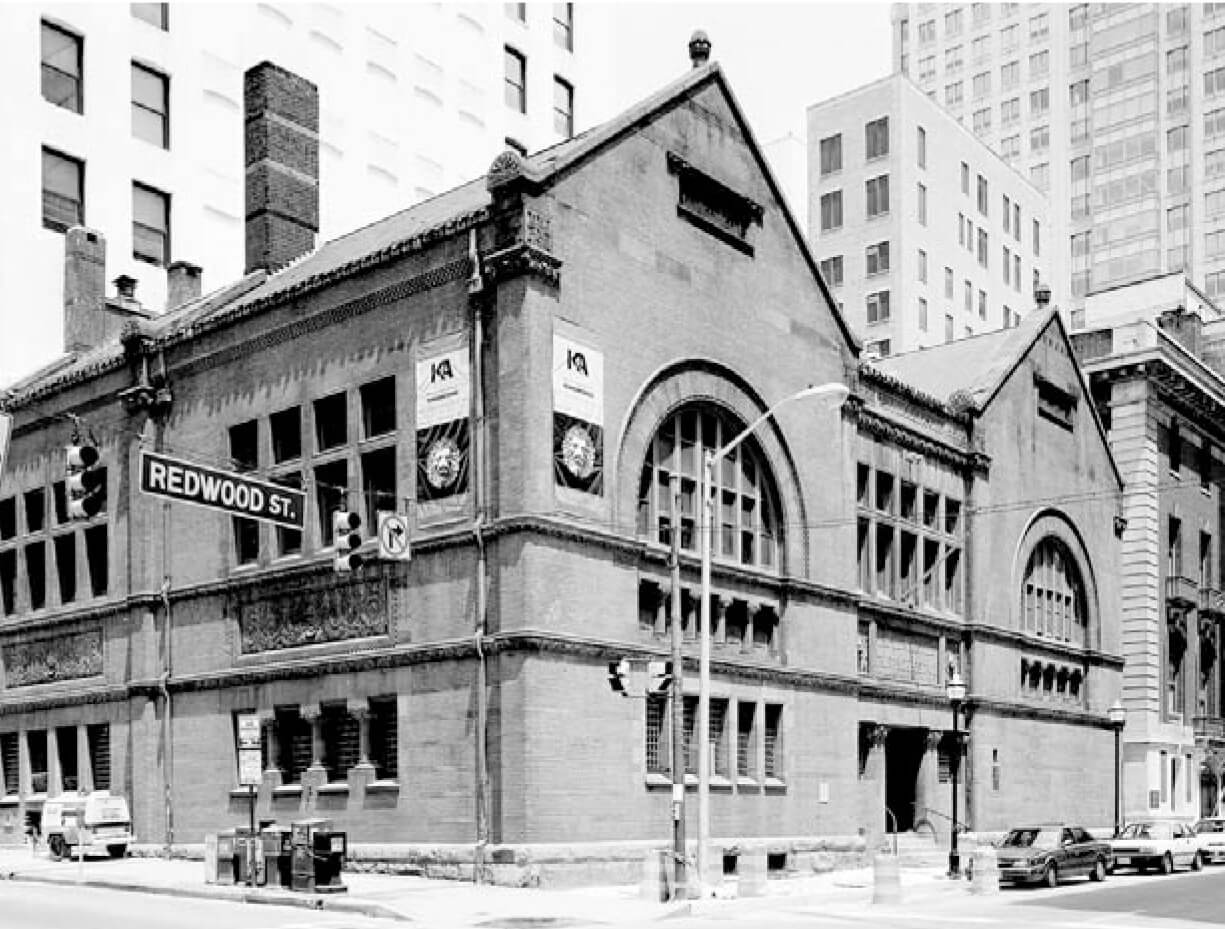

It started on Sunday morning, February 7, 1904, supposedly when a lighted cigarette was dropped through a grating in front of the John E. Hurst Company’s warehouse, located on the southeast corner of German (now Redwood) and Liberty streets. The dry goods stored in the basement were soon in flames and within ten minutes the building literally exploded.

In the 30 hours that followed, the fire, fanned by a southwest wind, consumed 140 acres of commercial property and destroyed 1,343 buildings. Some 2,500 firms were temporarily out of business. Few deaths resulted from the fire but the monetary losses were estimated at from $125 to $150 million.

Four days after the fire, while the engineers were still poking about in the surviving buildings, and the wreckage continued to smolder and occasionally burst into flames, the city was establishing the means of beginning again. Mayor Robert M. McLane appointed an Emergency Committee to deal with the burnt district, patterned on the one assembled after the Chicago fire of 1871.

It was composed of leading bankers, lawyers, politicians, architects and engineers, including some who later became prominent members of the Engineering Society of Baltimore: Mendes Cohen, Frederick W. Wood, President of the Maryland Steel Company, and Frank A. Furst, a contractor and political leader.

Founding

1905

The timing of Mr. Quick’s original idea to form a professional organization of engineers was significant.

In early February 1905, Alfred M. Quick, water engineer for the City of Baltimore, and the four other municipal engineers, decided to form a professional association. They issued invitations to 24 prominent engineers in the city, most of whom gathered on February 24th in the Mayor’s reception room at City Hall where they agreed to form a temporary organization. Mendes Cohen, an outstanding civil and railway engineer, was elected chairman; Mr. Quick was the secretary.

The Engineers Club of Baltimore was then established, membership opened to all engineers, and a committee set up to draft a constitution and by-laws. Officers were shortly elected, and within a few months, the club was meeting in its own quarters in the Woman’s Exchange Building at Charles and Pleasant streets. Its first president, D. D. Carothers, was chief engineer of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad.

The timing of Mr. Quick’s original idea to form a professional organization of engineers was significant—it was the first anniversary of the great Baltimore fire. He felt that the intensive re-building of the city already under way and the anticipated program of public improvements about to begin, both involving engineers to a great degree, favored the formation of a society that could extend and coordinate their services.

Roads, Water, & Piers

1906

The newly formed society helps guide and shape Baltimore’s rebuilding of it’s Sewage & Water Treatment systems, acquisition of property on the harbor’s waterfront, and widening and evening of its roads.

“The first thought was not how to simply restore the city, but how to make a greater one,” said the report of the Burnt District Commission, set up to implement the recommendations of the Emergency Committee. “Many of the buildings used for warehouses and other business purposes were old residences converted to such uses, occupying a great amount of space, but not at all suited to the economical transaction of business.

“The streets were wide enough, no doubt, for all the demands of long ago, but year after year they had become more and more congested. . . The wharves were in even worse condition, many of the docks being nothing more than mud holes, and so narrow that no modern vessel of even moderate size could get beyond the ends.”

Widening and leveling the streets and rebuilding the waterfront were two of the Emergency Committee’s major recommendations. Another was the establishment of building heights and laws. Mendes Cohen served on the sub-committee on street improvements (and fought, as a property owner, the proposed widening of Baltimore Street). However, Light and Pratt streets, and Market Place, among others, owe their present width to the Burnt District Commission’s work.

Frank A. Furst chaired the subcommittee on removal of debris; Frederick W. Wood was a member. The group recommended storing between 200 and 300 million reclaimable bricks and using the others to raise street grades and fill piers. The rest were to be dumped outside the city. Some of them ended up on the Patapsco flats in South Baltimore.

The profile of piers in Baltimore’s inner harbor, site of current re-development, is also due to the work of the Burnt District Commission, along with the harbor engineer. The city, which prior to 1905 had owned almost none of the waterfront, used money from the sale of its interest in the Western Maryland Rail Road Company, which took place just before the fire, plus loan funds, totaling almost $7 million, to purchase the property. Eight new piers, from 150 to 1,450 feet, and stretching from South Street almost to Central Avenue, were constructed. Some represented the first all steel and concrete piers built in this country.

While the resistance to the widening of Baltimore Street and the postponement of other segments of the Burnt District Commission’s program dampened the enthusiasm of some residents, most Baltimoreans were eager for further improvements in their city. In December 1904, the new mayor, E. Clay Timanus, called a general Public Improvements Conference with delegates from all sections of Baltimore. Frank A. Furst served on the executive committee. The conference endorsed loans for sewers, paving and other municipal improvements and the next year the voters approved them.

Baltimore was one of the last major cities in the country to acquire a sewer system. Before the fire, privies and water closets drained into backyard cesspools, bath water and kitchen waste were thrown into the streets, and the residue, flushed by rain and guided by Baltimore’s topography, ran down into the harbor which, according to one writer, “in the summer was frequently a stinking mass of decaying garbage and other pollution.”

Three times prior to 1900 commissions had been established to study and propose remedies for these unsanitary conditions. The last was headed by Mendes Cohen, whose group studied sewage systems in Europe and the United States. But by this time, the issue had become embroiled in politics and there was little action. (According to club member Abel Wolman, this was due in part to the resistance of the firms that emptied the cesspools, which for years had fought the bond issues.)

At any rate, ground was broken October 22, 1906 for the initial $10 million separate storm and sanitary sewage system, including a disposal plant on Back River. By 1911, when the Back River Sewage Treatment Plant was put into operation, with 12 acres of filters, Baltimore had completed 181 miles of sewers, drains and connections. The Back River plant was designed by club member Ezra B. Whitman. Part of the project was covering the Jones Falls (“practically a great open sewer,” according to Mr. Whitman) with a “fine broad street.”

Water supply was another item naturally brought to mind by the fire. A new high pressure service was added downtown, but general improvements were necessary because siltation had severely reduced the capacity of the city’s reservoirs. By 1911, when Mayor James H. Preston named Mr. Whitman to succeed Mr. Quick as the city’s Water Engineer, it had been 30 years since the water supply system had been substantially improved, and there was still no filtration plant.

In fact so old was the system, dating back to 1804 when a private company had been formed to supply the city with water, that Mr. Whitman remembered seeing the early wooden pipes—locust or spruce pine logs with a bored four-inch hole for carrying the water—being taken up from the streets.

The municipality had acquired the company in 1854 and by 1862 had built the dam at Lake Roland along with Hampden and Mr. Royal reservoirs. Druid Lake was added about ten years later, supplied by a conduit from the Hampden reservoir.

“This water, piped through a small distribution system, was improved by sedimentation and clarification but was innocent of filtration and sterilization,” said Gustav J. Requardt, a prominent club member, who, with Mr. Whitman, later formed one of the city’s major engineering firms. “Muddy water flowed from the spigots and eels and small fish regularly surprised the users.”

By 1881, the city had built the initial 25-foot marble dam at Loch Raven on the Gunpowder Falls, and a 12-foot diameter unlined tunnel through rock to the new Montebello and Clifton reservoirs. Those were the facilities inherited by Mr. Whitman when he became Baltimore’s water engineer in 1911. He was, said Mr. Requardt, “the designer and originator of Baltimore’s modern water system.”

The new 188-foot dam at Loch Raven and the first 125-million-gallon-per-day rapid sand filtration plant at Montebello were added under Mr. Whitman’s regime. They were in service by 1915, when the Jones Falls was discontinued as a source of water supply for Baltimore.

Move to Arundel Club on West Eager Street

1912

The Engineers Club moved from the Woman’s Exchange to the Arundel Club on West Eager Street and defined its purpose.

The Engineers Club moved from the Woman’s Exchange to the Arundel Club on West Eager Street. And, it defined its purpose which was, according to the charter granted in 1911, “the promotion and advancement of the arts and sciences connected with engineering of every kind, architecture, geology, metallurgy and chemistry by the maintenance of club rooms, lecture rooms and reading rooms for the benefit of its members and others interested in the advancement and discussions of said arts and sciences. . . and for their social intercourse."

Social activities were increasing among the membership, which had grown from 30 to 240. They heard frequent outside speakers, took field trips to nearby industrial plants and new engineering structures, held formal dances. The club had begun to take a stand on legislation and other matters affecting engineers and public works. And in January 1912, it started the Monthly Journal of the Engineers Club of Baltimore.

Membership Growth

1921

With 615 members a move to the Commerce Trust Building on the southeast corner of Light and Redwood streets was needed to accommodate the increased membership.

In 1921, the club moved again, with 615 members, to the Commerce Trust Building on the southeast corner of Light and Redwood streets, where a dining room was opened and a tradition of Wednesday noon lunches and lectures was begun. Like the magazine, it has lasted down to the present.

The Engineers Club publication continued, sporadically, until about 1921.

Baltimore Engineer

1926

In 1926, a new publication, The Baltimore Engineer, was started.

In 1926, a new publication, The Baltimore Engineer, was started. Editor Henry G. Perring’s initial statement of purpose is a model of straightforwardness:

“The Baltimore Engineer now makes its first appearance. It greets you and will try from time to time, to interest you—not always—only occasionally.

“The Baltimore Engineer, as an institution, will be perfect. As far as the human factor is represented in its editorial staff, it will be nearly human. That is to say, interesting—drab—peppy—dry—hopeless—helpful—good—rotten—consistent or not—and all the rest that goes with the state of the liver of the editor—or the reader.

“If you like us, we will be glad of your recommendations. If you don’t like us, keep quiet. We don’t care whether you like us or not. We would rather be read and disapproved, than approved and not read.”

One must assume that the magazine was read since it is still being published, after almost 55 years, with the same basic formula: articles on local subjects by local authors, and notices of professional activities of interest to its readers. With the exception of one brief period between 1948 and 1952 when the magazine degenerated to filler material, a series of editors who evidently shared Mr. Perring’s taut principles have kept it interesting.

Move to Bixford Building

1932

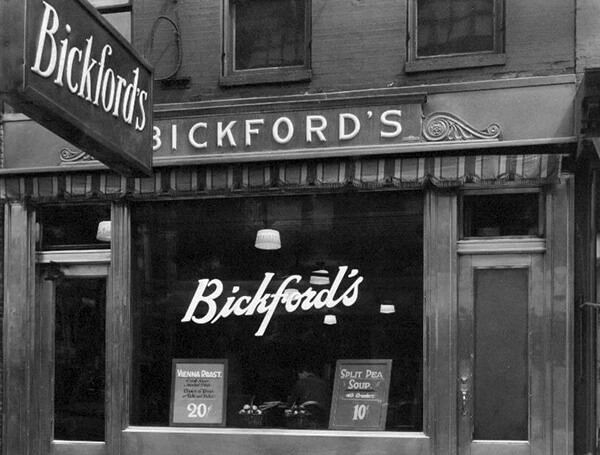

Move to the Bickford Building at 6 West Fayette Street and prominent speakers for club members.

By that time, the club had moved again, with 500 members, to the Bickford Building at 6 West Fayette Street. The members leased two floors and had a large dining hall, lounge, and library, which at the time contained 2,000 volumes and more than 300 pamphlets. “Our reading rooms now furnish with regularity three daily newspapers and 39 periodicals of interest to engineers, and further, they are being actively used,” reported The Baltimore Engineer.

In February 1932, John F. Stevens, the former chief engineer of the Panama Canal, gave a well-attended talk on the subject. And as chess was a popular pastime among the members, later tha month U. S. Chess Champion F. J. Marshall gave a demonstration at the Engineers Club, taking on several members and those of other clubs. After 2½ hours, “he appeared to have the situation well in hand,” said the editor of the magazine with a trace of chagrin. “When due consideration is given to the quality of the opposition, this is the finest exhibition that we can recall by a master in Baltimore during the past ten years. In the exhibitions of other years at the Baltimore Chess Club, masters have usually lost or drawn several boards.”

World War II and the Engineers Club

1940s

Move to the Bickford Building at 6 West Fayette Street and prominent speakers for club members.

The engineers, with the rest of the country, weathered the depression. “In the matter of finances, the club has suffered greatly the last year,” President Requardt said in 1934. “This has been due to loss of membership and the inability of many of our good members in the matter of payment of dues. The construction industry has suffered vitally during the national depression and that means that our membership has suffered greatly in loss of positions, opportunities for selling materials and services. . .”

In the 1940s, World War II had the opposite effect: “Whereas during the depression years, many of the men with engineering education were forced to find employment in other lines of work, the present conditions are pressing into service all of the available men in any way fitted to engineering positions,” said Herschel H. Allen, the club’s new president, in June 1942. The following year found 41 of the club’s 632 members serving in the armed forces. Those who stayed at home could read, in the club’s publication, about emergency transportation and incendiary bombs.

Plans for a New Headquarters

1950s

After its 50th anniversary, the Engineers Club had expanded to occupy three floors of the Bickford Building. It became obvious in 1956 that the club would have to move and the work began to find its new home.

Alfred M. Quick and Thomson King prepared a history of the Engineers Club for its 50th anniversary in 1955. (George K. Fitch, a frequent contributor to the magazine, covered the later years.) By 1956, the Engineering Society of Baltimore had expanded to occupy three floors of the Bickford Building; it became obvious that year that the club would have to move. The membership had been declining for some time, and dues had been raised with no commensurate increase in services or facilities. Besides, the Charles Center project was gathering momentum, and it was likely that the club’s headquarters for the past 30 years would be demolished. (It was; One Charles Center now occupies the site.)

Then began one of the more confusing periods in the organization’s existence. The club first considered constructing its own building. Several sites were explored, including one at Howard Street and Park Avenue.

In May 1958, Arthur M. Gompf, chairman of the Permanent Quarters Committee, reported that the proposed new building would cost roughly $2 million. The club decided that was too expensive, and began a search for suitable quarters for sale or rent.

The engineers considered a building at South and Redwood streets, for sale at $300,000 in 1959, but rejected it in favor of the structure at 307 West Fayette Street owned by the Fraternal Order of Elks. The Engineers Club offered to purchase that property at about the same price.

For reasons that were never made clear, the Elks, after showing early enthusiasm for the arrangement, rejected the offer in February 1960. An attempt was made to rent part of the Elks Building. That too appeared to be a certainty, so much so that The Baltimore Engineer for November 1960, devoted considerable space to the move. But that scheme foundered as well on the refusal of the Elks to allow the Engineers Club to transfer their liquor license. The two organizations then went back to discussing a sale, but as of December 1960, could not come to an agreement.

“We are now back where we started,” said A. Russell Vollmer, the Engineers Club President at the time. “The merry-go-round has made a full circle and this administration is dizzy from the ride.”

A New Lease

1961

As time was running out on its current home, the Engineers Club moved to lease a forgotten historic gem.

Meanwhile, time was running out. The club members were told that demolition of their West Fayette Street building would begin February 1, 1961. However, Bernard L. Werner, then the city’s director of public works and an Engineers Club member, had been told by another city official that an agreement to lease the municipally-owned Garrett- Jacobs Mansion would be favorably considered by the city administration. Club member Robert Deitrich also played a part in the arrangement.

The city had bought the mansion with the intention of tearing it down for the planned expansion of the Walters Art Gallery on Mount Vernon Place. However, those who opposed the destruction of the mansion, led by attorney Douglas H. Gordon, Jr., defeated a $9 million bond issue for the Walters project in 1958, as well as a second, scaled-back $4 million plan in 1960.

On January 1, 1961, some of the club’s officials explored the Garrett-Jacobs Mansion, which had been vacant for some three years. It was not an inspiring sight. Water from overflowing gutters had run down the brownstone façade, streaking the empty windows with dirt. The interior was cold and dark. “The drawing room had ice about a third of the way across the parquet floor from a leak in the roof,” remembered Mr. Gompf, the club’s new president, who was one of the party that groped their way through the empty building.

A few days later, the Board of Estimates approved a lease—unfortunately for the wrong property, the house at One West Mount Vernon Place. A new lease was drawn up to rent 7-9-11 and 13 West Mount Vernon Place to the Engineers Club for $6,000 a year. It was signed January 23, 1961.

In February 1961, the club reopened in its new location. The members of the Board of Estimates and other city officials were impromptu guests at the first noon luncheon, where Mayor J. Harold Grady proclaimed “a renaissance in the city’s economical, civic, and cultural life.” “We’ve Moved,” announced the March issue of The Baltimore Engineer, and this time they meant it.

Garrett Jacobs Mansion Purchase

1963

After seeing membership decline in its former home, the move to the Garrett Jacobs Mansion offered opportunities not previously explored.

Meanwhile, another committee had been studying the club’s aims and objectives. In their 1961 report, they cited a long-term decline in interest in the organization, which had become essentially a luncheon operation at the old location. Disbanding had been one of the alternatives considered.

Of the roughly 700 members at the time, only the 200 who regularly used the dining facilities at the Bickford Building received a good return on their dues, the committee said. “In no sense can the Engineers Club be called an engineering center for the Baltimore community of engineers,” they added. Among their recommendations were establishing closer ties with local industries and engineering schools, starting an education program, and hiring an executive director.

But the sense of “negative progress” cited by the committee in the early sections of its report had been largely dispelled by the move to the Garrett Jacobs Mansion. “For the first time in our history we are housed in quarters of which we can justly be proud and which afford the facilities necessary to make our considered contribution to the entire engineering community,” the committee concluded.

The Walters Art Gallery having been persuaded to relinquish its claim on the property, the Engineers Club bought 7-9-11 and 13 West Mount Vernon Place in 1963 from the city for $155,000. The club later sold 13 West to the Estelle Dennis Dance Studio. The mansion was renamed The Engineering Center of Baltimore.

Membership Expansion and a New Name.

1965

In 1965, the Engineers Club moved to expand, changing its name and its bylaws to help attract more members.

In 1965, evidently for tax purposes, the club changed its name to The Engineering Society of Baltimore, Inc. And at this time its bylaws are revised to expressly allow for women and minorities to have access to membership.

In the years following the move, the membership almost doubled and the club’s activities expanded accordingly. Women were admitted, a Women’s Auxiliary was formed, and luncheons and dinners in the new headquarters became a succession of festive social occasions: cookouts and oyster roasts, concerts and dinner dances, cocktail, theater, and “feather” parties. (The last was described as “a bingo game for turkeys;” it evidently dated from the time that lotteries were illegal, and was a perennial favorite.)

An executive director, Arthur E. Clark, Jr., was hired. The Center’s education program was initiated in 1961 with four courses: Professional Concepts of Engineering; The Legal, Social, and Economic Phases of Engineering; English for Engineers; and Speed Reading. The members undertook the renovation of the building’s floors, windows, and heating and food service facilities.

The Society began the annual celebration of Founders Day, commemorating their origins, and marking the presentation of an award to an outstanding member, in the early 1960s. Engineers Week is celebrated in February when an annual Civic Achievement Award is presented to a prominent member of the community at large.

Heritage Dinner

1967

In 1967, the first Heritage Dinner was given; which became an annual event. It was a black tie affair held in winter in the marble and mirrored dining room.

In 1967, the first Heritage Dinner was given; it too became an annual event. It is a black tie affair held in winter in the marble and mirrored dining room. It provides, according to Mr. Gompf, chairman of the Heritage Dinner Committee, “the opportunity to enjoy the mansion in the kind of social setting for which it was built.”

The Heritage Dinners have produced funds which, augmented by additional monies from individual members and the Society, have been used to restore the building. Proceeds from the dinners have bought the furnishings or the first floor entry, lounge, and library and have been used to renovate the auditorium and the former family dining room, which is now the Society’s board room

Heritage Dinner

1974

The courtyard, formerly the mansion’s enclosed conservatory, was a major renovation project, completed in 1974.

The courtyard, formerly the mansion’s enclosed conservatory, was a major renovation project. The original roof had been removed some time before the Society’s occupancy, and the deck structure had deteriorated. The project was supported by three years’ worth of Heritage Dinner proceeds plus additional loan funds. Demolition began in the summer of 1973. The handrails and stairs were restored; the new courtyard was dedicated in May 1974.

It was the largest single restoration item the Society undertook since its move. On the day the courtyard was dedicated, Society President F. Pierce Linaweaver said, “We are making every effort to maintain and restore [the building], not as it was. . . but to create an engineering center where we may meet and, on occasion, invite guests to enjoy with us this splendid legacy from the past.”

75th Anniversary

1980

The Engineers Club had over 1,100 members with more than seventy percent of whom were engineers or architects, as well as twenty-two associate societies—including the representatives of the basic chemical, civil, electrical and mechanical engineering professions.

The Engineers Club had over 1,100 members with more than seventy percent of whom were engineers or architects. These comprised eight membership classifications. Important among them are the Sustaining Member group of 44 firms and organizations that employ engineers or engineering services and which, over the years, made contributions that helped make The Engineers Club possible.

Twenty-two associate societies—including the representatives of the basic chemical, civil, electrical and mechanical engineering professions—were active and communicated through the Associate Council. One of the additions near the 75th Anniversary was the Society of Women Engineers.

Some of the society’s functions can be gathered from the names of its nineteen committees, comprising 187 members and including By-Laws, Civic Affairs, Education, Entertainment, Financial Advisory, Founder’s Day, Heritage, House, Membership, Memorial Scholarship Fund, Office, Past Presidents Advisory Council, Publications, Publicity and Hospitality, Public service, Speakers, Towson and Columbia sections and Young Members.

Growth Struggles

1990s

With member demographics shifting and maintenance costs increasing, the ESB looks to adapt and move forward. The Garrett Jacobs Mansion Endowment Fund is founded and the Fire Ball begins.

“We discovered in 1992 that the Club could no longer support the building,” said William O. Boland, another former ESB president (1995-1996). Realizing that they needed to adapt in order to survive, the leadership of the Engineers Club has undertaken several major changes over the past decade. The first was the recognition that they were no longer, strictly speaking, an Engineers Club. “In sum and substance, The Engineering Society of Baltimore, Inc., has gradually but steadily become more of [a] generalized downtown business and professional society,” ESB president Martin Jay Hanna, III, wrote in the Club’s publication in 1994.

Significantly, that year The Baltimore Engineer was reorganized as Quick’s Professional Journal, a monthly tabloid. It still carried engineering articles, but the editorial emphasis was on the history of the mansion and the club’s relationship to it. In late 1999, Quick’s again became an 8 ½ x 11” magazine, and in 2002, a quarterly whose contents consisted mainly of a calendar, photographs, and club news.

The Garrett-Jacobs Mansion Endowment Fund was incorporated in 1992 as a 501©3 non-profit organization to raise money to repair and preserve the building. The fund became active in 1995 with the help of Mr. Boland and Donald J. Blum, executive director of the Engineers Club (1986-1998).

Any business venture needs one strategic asset and the Engineers Club’s is the mansion, wrote Mr. Boland in the July 1995 issue of Quick’s. Its preservation was to be their top priority. A professional fund-raiser was hired. Early in 1996, architects Kann and Associates were brought in to write a Historic Structures Report for the mansion and a master plan for its restoration.

The Garrett-Jacobs Mansion Endowment Fund organized a $6 million capital campaign to pay for the restoration program called for by the master plan. A new social event, the Fire Ball, and art auctions were held to raise money. The fund succeeded in raising $500,000, most of which was applied to a major restoration of the mansion’s brownstone façade, completed 1998; the estimated cost was $600,000.

The heating and air-conditioning systems were dealt with next. More fundraising events, the Boiler Blasts, were held to raise money. Working with members of the American Society of Heating, Refrigeration, and Air Conditioning Engineers (ASHRAE), one of the Engineers Club Associate Societies, and particularly member Bruce T. Votta, the 50-year-old boilers were replaced with a new heating plant. Manufacturers donated components, mechanical contractors contributed services, and a volunteer engineer served as “clerk of the works.” The total amount in donated services and materials came to $500,000, according to Mr. Leach. Through replacing the heating plant and improving the building’s air conditioning systems, the mansion’s operating costs were significantly reduced. The Herculean fundraising effort funded many projects but funding of the master plan remained illusive.

Expansion of the Kitchen and Third Floor Renovations.

2000

With a growing emphasis on the food and beverage operations, an expanded kitchen and kitchen support systems were moved to the Main Level. And a new tenant help renovate former servants quarters on the third floor.

In 2000, then ESB president Leach reported in Quick’s a more pressing need: “Analysis showed that more and more of the Club’s revenue is dependent on revenue generated by food and beverage sales. These sales are completely dependent on our present kitchen and kitchen support spaces, which are completely inadequate and at the brink of failure. Such a failure could literally put us out of business.” Ninety percent of the club’s current revenue is derived from wedding receptions and other large private functions. A committee recommended relocating the lower-level kitchen to the first floor Gallery at an estimated cost of $700,000. This was less expensive than the $1 million estimated cost of replacing the kitchen in its current location, which would also have meant shutting it down. The move, financed by borrowed funds, was accomplished in 2001 by constructing a shell inside the Small Gallery to protect the room’s ornate decoration and installing the new kitchen; a rear freight elevator was also added. This made it possible to restore the gallery at a later date if the kitchen were to be relocated into a new structure.

Another accomplishment of the millennium year was a new partnership with the Walters Art Museum. At a cost of $150,000, the museum renovated the former servants’ and guest quarters on the third floor of the mansion, an area that had been primarily devoted to storage, for use as office space. The Walters moved its twelve-person membership and planned giving staff into the renovated office suite, which includes a bathroom and kitchenette, and a new entrance from 5 West Mount Vernon Place. The museum needs the space, which they also use for staff retreats and teaching sessions, according to ESB member Gary Vikan, director of the Walters Art Museum; the Engineering Center benefits from their lease payments.

Centennial Celebration

2005

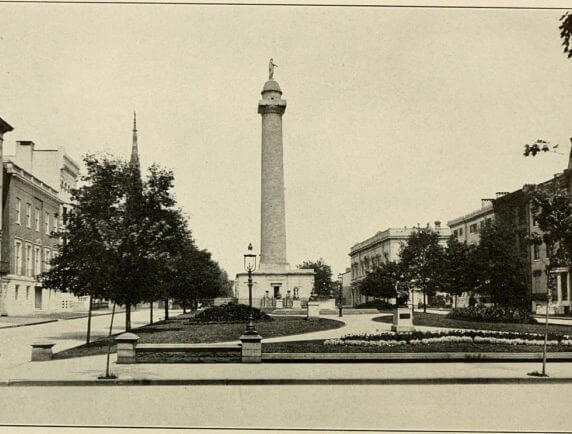

The party began with the 2004 Baltimore Monument Lighting, the celebration and continued right through the 2005 Monument Lighting.

The Club’s Centennial Celebration had its official start at the Monument Lighting Party in December 2004. Mayor Martin O’Malley was an honored guest and personally presented a Proclamation from the City. Despite a snow storm, the 100th anniversary luncheon held on February 24 was well attended, where the Centennial Plaque was unveiled and a Proclamation was received from Governor Erlich. Snowed out that day was the presentation of a plaque to the City of Baltimore commemorating the founding of the Engineers Club to be permanently displayed at City Hall in the Mayor’s Conference Room where the Club was originally founded by Alfred Quick. The Heritage Dinner was renewed and attended by nearly 100 people who thoroughly enjoyed a formal four-course, elegantly served meal with a different wine with each course. The revelers were greeted as they arrived by Mrs. Garrett-Jacobs, portrayed by Ms. Emma Carroll and Alfred Quick, portrayed by President Dick Magnani. The dinner raised nearly $4,000 toward the restoration of the two Tiffany windows on the spiral staircase. Other events planned for the Centennial included a day at an Aberdeen Ironbirds game, the Garrett Hat Tea (formal high tea with possibly the biggest and best display of hats ever), the entombment of the time capsule and finally the closing ceremony at the Monument Lighting Party in December 2005 with honored guest Donald Schaeffer.

Pandemic Impact & Vision for the Future

2020

With the advent of the Covid-19 pandemic, the ESB refocuses on the member experience and its roots in the engineering community to ensure its future.

As the Engineering Society of Baltimore continued to rely heavily on catering and food and beverage it has been particularly hard hit by the pandemic which placed severe restrictions on in person gatherings (including their prohibition) for over an 18 month period.

The Engineers Club’s membership, after reaching a peak of 1,200 in 1995, had declined to then levels of ~400 members, less than before the move to the Garrett-Jacobs Mansion in 1961.

More revealing is the change in the makeup of the membership. Forty years ago, seventy percent of the Engineers Club’s members were engineers and architects. In January 2020, the situation was close to the reverse: almost two thirds of the members were non-engineers and 18 percent were women. There are several reasons for this turnabout.

Engineering firms used to be concentrated in the center of the city. But over the past four decades, the lure of the suburbs has continued to attract many of these firms (as it has other businesses and residents), thus weakening the connection between the engineers and their headquarters.

Faced with these challenges the Board President Jeff Lange created the Emergency Strategic Committee, which included future presidents Rosanna La Plante and Harry Stephen. Together the committee worked to restore historic contacts in Baltimore’s engineering and construction communities.

To foster this, a Vision Sponsorship program was created for these individuals to make multi-year commitments to help restore the club’s membership as it had fallen to levels not seen since the great depression. Their success in garnering the support of these Vision Sponsors has allowed the ESB to survive the pandemic and work to engage the revitalized membership for the path beyond.